Giant Redwood Tree Facts

One giant sequoia tree, nicknamed The President, in the Sequoia National Park, California is estimated to be 3,200 years old. It stands at 75 to 80 metres tall and consists of 1,500 cubic metres of wood and bark.

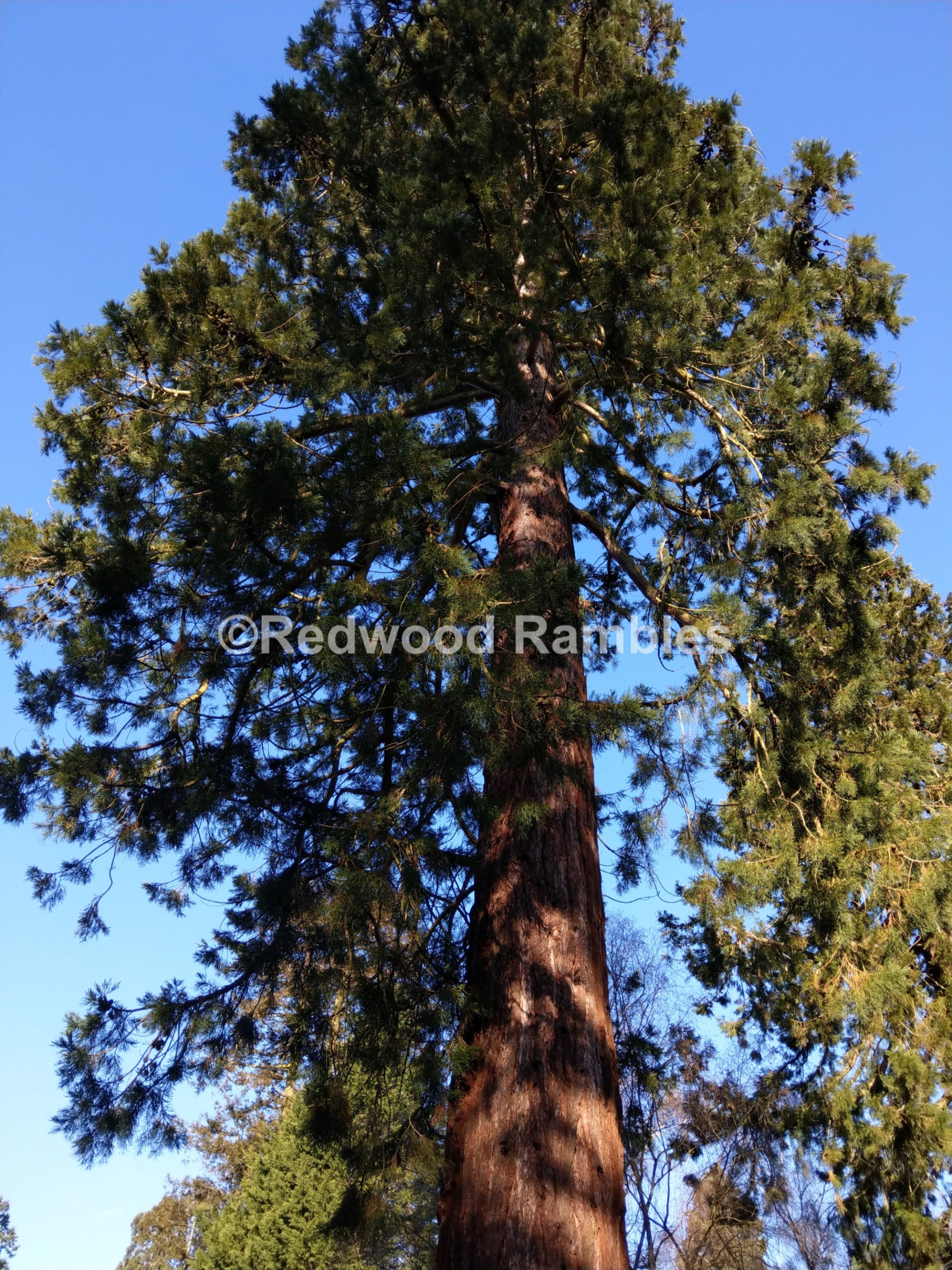

Their bark is soft, fibrous and spongy, reaching a depth of 300 mm in some instances, and is fire resistant. Despite its thickness, if you tap on the trunk of a Redwood tree, it sounds hollow.

Giant Redwood trees originate from areas that experience earthquakes. In order to survive these, and other events, the trees have developed a clever coping mechanism. In extreme situations where a tree starts to lean due to shifting soil, floods or unilateral weight bearing, it can increase its growth on the downhill side to prevent it from toppling over. Redwood trees that appear to be leaning are not an uncommon site.

Despite having the potential to grow as tall as a 35 storey building, the roots of redwood trees are not as deep as you would expect; often reaching a depth of only 1.5 to 2 metres. Instead, the roots gain strength by intertwining, and even fusing, with roots from other redwood trees, giving them a tremendous combined strength. They thrive in a community that supports its members both structurally and nutritionally. As old trees die they decay and release the nutrients they have absorbed over the centuries back into the community of trees through the root system. The root system then sends up a new sprout to replace the dead tree.

Giant redwood trees originate from areas of the world which are also prone to fire and drop their lower branches to prevent fire spreading through the canopy. Fire is actually a part of the lifecycle in their natural habitat. The heat produced in a fire results in the cones drying and opening up to release the seeds onto convection currents for dispersal. The flames clear the forest floor of competing plants and the resultant ash acts as a fertiliser to help the new seedlings grow.

Male 'flowers' and female cones can be found on the same tree. The male 'flowers' shed pollen in March to fertilise the seeds of the female cones. The cones stay on the tree, ripening in the second year before dropping.

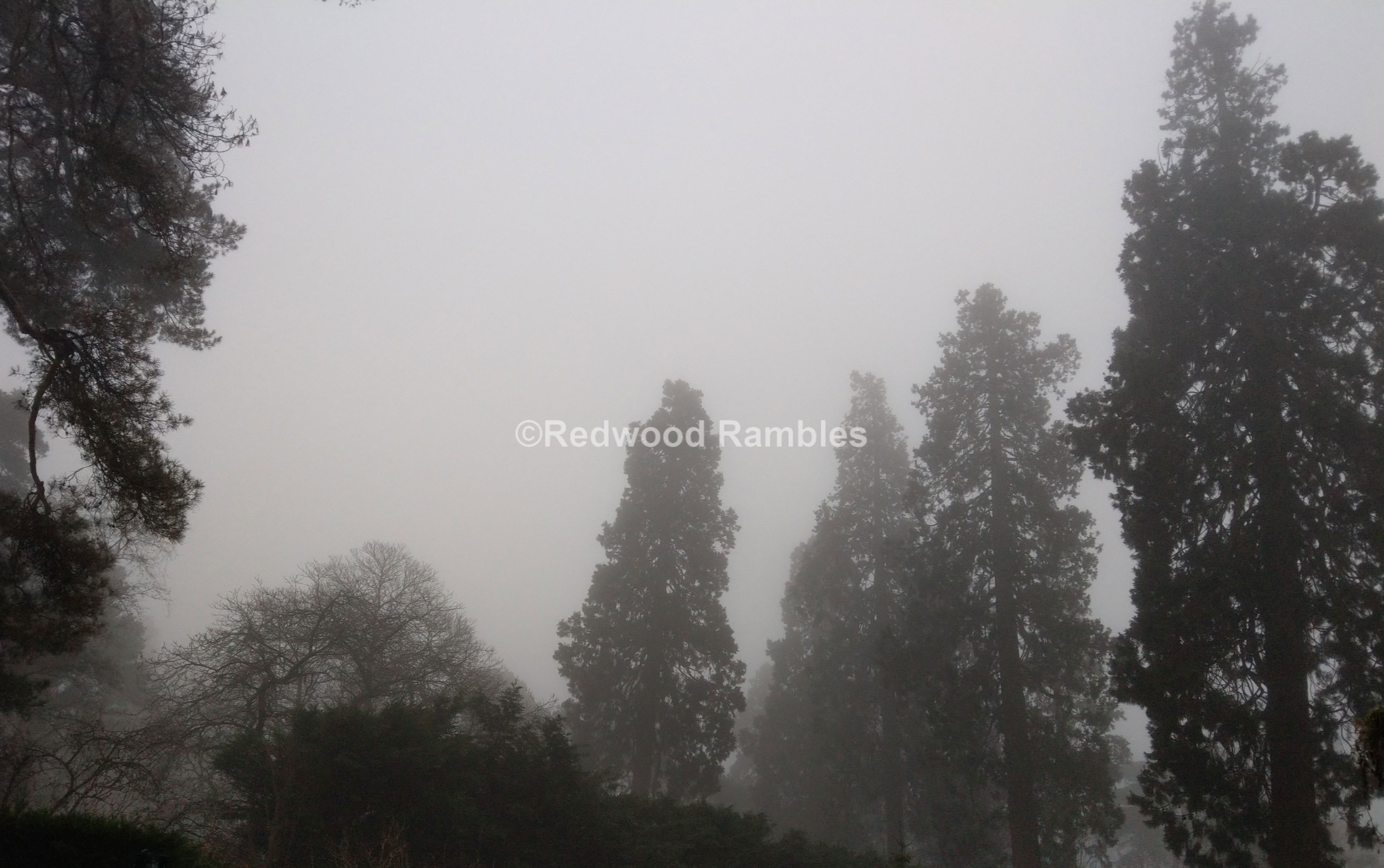

As you would expect for such large trees, it is said that giant redwoods transpire between 2000 and 3000 litres of water per day. Strangely it is also their size that enables them to survive in dry seasons, extracting moisture from fog and mist through condensation forming on their enormous surface area and dripping/trickling to the roots below. Some redwood groves even generate their own rainfall by trapping fog in the canopy.